[This is an excerpt from a post in Fred Wickham’s Bullseye Rooster. Dan is Fred’s brother, and Buzz is his business partner in a small business. I totally agree with this idea.]

Two years ago, Dan and Buzz were heartened by the election of Obama. Aside from all the marvelous change he would be bringing to America and the world, he promised to help small business. So it was a little bit odd when he put all the big bankers into the business policy jobs. It turned out to be worse than just odd, it’s worse than nothing. No small business loans. No small business investment strategy at all. The large corporations are getting fatter and fatter, owning more and more, and actually buying out small businesses for a song. The inventors and entrepreneurs have been sucking hind tit. All the while, the stock market is going great. But jobs are not being created. It’s all about trading now.

Paper trading — actually not even paper. Traders are scoring big with trades that last only a microsecond. A sufficiently well-heeled investor can buy and sell the same stock in less than a second and, through some sleight of rational thought, become a good deal richer. All in the time it takes to cough in the face of his intern.

I asked my brother if, as a small businessman, he could have any wish, what would it be?

“Get rid of the stock market,” he said. I gave him a get real look, then he continued. “Get rid of the trading system as it is currently structured. These bastards are trading lickety-split, but there’s no incentive for them to hold onto their investments. The stock hiccups, they take their profit and bail. The point of the market, old-fashioned as it may sound, is to capitalize a venture that you see as a viable addition to the economy. The designer, the workers, the sales staffs, the entrepreneurs and, yes, even the consumer — these are the people who must benefit to have a market that inspires production.”

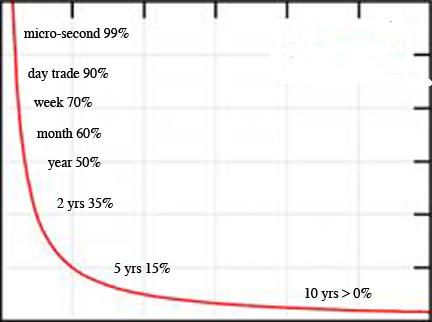

With that, Dan outlined his cure. Those who buy and sell stocks in a micro-second, should pay a 99% capital gains tax on their (excuse me while I clear my throat) earnings. Yes, outrageously confiscatory in order to stop this outrageous practice. A day trade, 90%. Sure it’ll piss off the day traders on their laptops, but it should open up a few tables at Peets when these guys get off their asses and find something productive to do. Hold on to your stock for a week, 70%. A month, 60%. Year, 50%. Two years, 35%. Five years, 10%. Ten years or more, zero percent capital gains taxes.

Certainly, this scheme would trigger outrage. The rich don’t even like to pay taxes on their Grey Poupon. But that’s the point. Propose it as it is. Let them scream. Wake the public up to what it is that investment is supposed to do for the economy, for the honest businessman, for the job-seeker.

I said, what would you call this? “Well, it’s based on an asymptotic curve — might as well call it asymptotic trading.”

Sounds good to me. Dan Wickham’s Asymptotic Trading. DWAT.

28 Comments

I love it.

And I don’t see how it could be implemented.

1) How would one transition to such a system without destabilizing things dangerously? (destabilizing isn’t inherently bad… that’s called “change”… it’s when things get changed in such ways that day-to-day living is seriously disrupted that there’s a concern).

2) How would one keep the money in the US markets, instead of having all the capital disappear to other markets? (I remember similar arguments used when new regulations are imposed, and mostly they’re fear mongering or appeals to ignorance. But in this sort of a change, I think it’s a legit concern.)

Missing here is mention that there is no captal gain in the first year. A stock has to be held a year to qualify for a capital gain. Under a year, a gain is taxed at regular rates. And only $3000 of loss can be taken a year. The rest gets carried over.

Another few misconceptions that probably need to be cleared up:

1. Most stocks are traded on secondary markets, meaning they don’t affect the companies they represent. So I’m not sure what the appeal of long term vs short term would be in this situation. In effect, this is merely gambling that other people will find a piece of paper (or an invisible data bit) as valuable as you think it will be in the future.

2. You are not allowed to sell, then immediately buy again using your gains. It takes several business days for your sell to clear (I can’t remember at the moment if it is 3 or 4, I don’t trade that fast). This means that in order to speed trade and make any significant profit, you would need an enormous amount of capital.

Assuming you trade 5 “microsecond” $10,000 trades per day and it is a 3 day window, that is $150,000 of liquidity that you can afford to lose that you must own in order to play. A 4 day window requires $200,000.

So, back to my question in #1, these points aside what is the appeal of long term vs short term investment to anyone? To me this is like saying if I buy a case of widgets and turn around and sell them for a profit, that is bad. If I buy a case of widgets, hold them for 10 years then sell them, that is good.

Ok, what am I missing?

TenThirtyTow wrote: “So, back to my question in #1, these points aside what is the appeal of long term vs short term investment to anyone? To me this is like saying if I buy a case of widgets and turn around and sell them for a profit, that is bad. If I buy a case of widgets, hold them for 10 years then sell them, that is good.”

Isn’t the “benefit” of enforced, long term investing motivational? The idea is to get the investor to not care much about individual boxes of widgets, but to care about the long term prospects of the company / corporation. Having shareholders care about making companies successful long term should, I gather, then lead to also motivating the management to care / focus profit potential on those elements in the company that leads to long-term profit.

It seems that currently the incentives are to care about immediate, even small, profits over long term gain, which then incentivizes the management to focus on those quick, immediate profits (instead of focusing on slower, steadier, profits).

I’m very much a layperson here, so what am I missing? Creating incentives to encourage long term profits (even at the sacrifice of some short term ones) seems like a good idea: such incentives create stable, long-lasting companies. (The only problem I could see is if the incentives went too far in the opposite direction, somehow incentivizing stability over necessary/reasonable innovation. But I don’t see how the idea in the main article would inhibit innovation.)

I’m sure there are pitfalls to this idea, but I do love the concept. And I’m really glad Dan’s name isn’t Tom.

My knowledge of the stock market is fairly limited, so I’m not going to bash the idea being proposed, or try to offer solutions to the problems you’ve all described. As far as I know, the point of stocks is to help promote the businesses we invest in. We buy a piece of the company, which takes that money and uses it to grow and become more industrious, raising its value, which then relates to bigger returns on the original investment. The idea of fast trading seems to be based on the idea of trading in futures which is more lucrative but more uncertain. The theory put forth would get rid of the less-stable investment practices by taxing them, while safer and more beneficial trading is kept as it is now.

Is this an accurate view of the market?

Long term gains gets all the special treatment. (spell that “tax cuts to the rich”). In 2008,my income of $20,000 was mostly from “qualified dividend” stock held over a year and capital long term gains. And my income of about $6000 doing taxes. I paid no tax. My clients with their $12,000 income who had to go to work (transportation) and give up time in her day was a tax payer. I sceamed and yelled to the group I met on-line supporting Obama. No one cared. Even though my income was low, I’m getting the “tax cuts to the rich” that I and others have been yelling about for nearly ten years.

It isn’t that I disagree with the result of the tax curve. No doubt it would cause people to hold on to stocks for long amounts of time. My question is, why is this better? If this is a solution to a problem, then I am unaware of what that problem is.

Let me briefly clarify how stock markets work for those that don’t know. When I buy Apple stock on the NASDAQ, I purchase X shares of AAPL. When this buy order goes through, I don’t buy this from Apple. I purchase this from some other person (or several other people) at whatever price I tell it to purchase at.

So if John Brown is selling 10 shares of AAPL @ 300/share and I put in a buy for 10 shares of AAPL @ 300/share, I can buy those shares. However, Apple doesn’t see any of that. My money goes directly to John Brown.

My investment remains $3000 until I sell it. If I sell it for more, I make money. If I sell it for less, I lose money. But similar to my purchase, the money I recieve has nothing to do with Apple. Now it is some other person paying me money for my Apple stock. If I hold the stock for 10 seconds or 10 decades, when I go to sell it nothing has changed other than the price of that stock. It is still some other person buying my shares for some price they feel is appropriate.

The reverse is true as well: nothing Apple does directly affects the stock price on a secondary market. If Apple quadruples business, the stock price doesn’t necessarily quadruple because they aren’t directly related. The stock price flucuates based only on what people are willing to pay for it.

Most stocks are traded on secondary markets. And these secondary markets are where you see these quick trades happening. We call them markets but the more accurate name for them is stock “exchange.” Any stock traded on a secondary market has nothing to do monetarily with the company. Only when stock is purchased from a primary market does a company receive money for stock purchased.

And when that stock is sold, it is typically sold on the secondary market. This is why I don’t understand why holding stock for 10 seconds or 10 years matters.

1032 is correct to an extent. With the exception of some special classes of stock, ie. preferred, warrants, etc., shares in the markets (DOW and NASDAQ)are not directly tied to the company per se. If you bought a TV from panasonic and you then took that TV and “traded” it in a flea market for a profit or loss, that is an uncomplicated version of the stock market. The flea market (traders) get a cut, but the buyer and seller trade money. The difference would be that stock is a share of ownership of something (you could sell shares of your TV) and if you accumulated enough shares you could then hold the majority of a company.

Once upon a time many decades ago, shares traded based more closely on value, now they trade on expectations of future profit. Shares without dividends are usually growth stocks and are traded entirly on expectations, while shares that pay dividends are big companies that don’t grow so rapidly like utilities and energy. Trading in these stocks is affected by dividend price and frequency and dividends are tied to the profitablility of the company. The more profit it makes the more it pays out in dividends which makes ownership of those shares more desirable.

As o the taxing of long term capital gains there is no up/down side to the company, but there is an impact on buyers and sellers of stocks. The mantra for investing is buy and hold for the long term, with the reasoning that over 10-20 years a good company’s stock will appreciate. The only time it effects a company in the long term period is if the company desires to raise additional capital to expand. The “new” stock offerings price will be tied to the current market for that stock. The company hires an outside investment banking firm who then assesses what value can be expected per the # of shares to be sold and affixes a price. If it’s a new class of stock or a new company it would be called an IPO (initial public offering). The investment banker acts as the salesman for the compnaies stock and offers it to the market at a fixed price. As soon as it is bought in the market the price will begin ti fluctuate and the ruless of supply and demand kick in. The compnay only gets the initial offering price, everything else is market driven.

That was entirely too long, sorry.

The problem with short term trading WRT the fundamental theme of this post as i understand it is as follows. As long as investors believe they can make more money investing short term by trading the secondary market they will not invest in small businesses.

Patriot: thank you for the explanation. I know I invest the “buy and hold” method. Love the preferred stocks. They take my money to build their Utilities or improve them. I get a guaranteed yield,doesn’t go up or down. I buy “below par” like a bond. When they don’t want to pay my 4.6% anymore, they give me my money back at par. The difference is my capital gain. Seems to be win/win for us all. Easier to understand than regular stocks. Most of Berkshire Hathaway is in preferred stocks.

“[N]othing Apple does directly affects the stock price on a secondary market.” Really? Then why do stock prices magically jump or dive whenever quarterly earnings are announced? Yes, we can quibble that this is an indirect effect rather than a direct, but the two events are so tightly correlated that such an argument is pedantic at best.

The problem is not the stock exchange in and of itself. The problem is how the stock exchange has drastically altered corporate cultures. The incomes of people at executive levels of major corporations are very closely tied to the market value of stock on those secondary markets. For instance, the CEOs of companies like Oracle, Google, etc., work for a “salary” of $1/year. In truth, they’re paid millions, just in other forms. As a result of this close connection, executives have the incentive to undertake actions that are best for the stock price. And, many times, those actions are not in the best interest of the average employee.

For instance, when I worked for Big Blue, the VP of our division exercised options to “purchase” around 50,000 shares of stock at $0 per share, each of which was valued at $100 at that point. Three months AND after this trade, the price was about $80/share. Curiously, the initial rise from $80 coincided with this VP killing thousands of jobs–1500 from one site, about 3000 or so total. (And that was just our division. That doesn’t include the other divisions that also shed thousands of jobs.) Apparently, janitorial staff isn’t needed. After working 60 hour work weeks, software engineers should sweep and mop their own damn offices if it helps to increase this VP’s bonus from $4M to $5M. This was a company that used to have a culture that kept employees for 30 years. Now, people struggle to make it to the 5 year point, just to get vested in the (very meager) pension.

But this culture goes beyond just this one company. I’ve heard plenty of stories about how executives used to take pay cuts when things got bad. Now, they just fire people until things get better, when they hire new people. While this makes for an efficient market and leads to great “productivity” numbers (because nothing is more unproductive than underutilized employees), it ignores the psychosocial impact of the layoffs. I had a friend that got laid off from the sales division after 20 years with the company. Five years later, she was working as a cashier at Barnes & Noble and living in her son’s basement.

The problem is compounded by mass involvement in the stock market. In the past 30 years, the culture of corporate America has changed to push everyone into the stock market. People used to have guaranteed pensions. Now they have volatile 401Ks. Trading firms advertise with promises of easy money in order to get suckers to invest their life’s savings in a volatile system. The increased capital simply enables investment banks to make bigger and more volatile bets.

So, while stock exchanges themselves are not evil, they have produced many unintended consequences that the vast majority of people would describe as evil.

1032 (and PSgt), you are mostly correct, but you leave out a few important facts.

Let’s start with the Panasonic TV example (and ignore for a moment that used TVs lose value through use, while stock does not). If in a secondary market (flea market) for TVs the price goes up, then Panasonic is able to get a higher price for new TVs that they produce. So when I sell my TV at a flea market, while Panasonic does not get any money from that transaction, it is not true that they do not benefit.

The same thing applies to stock. You already mentioned that when the company issues new stock, they are able to make money if the price of their stock is high. This is actually pretty important, as companies do issue new stock, maybe not all the time, but fairly regularly, especially if they are growing.

In addition, you forget that most companies hold onto quite a bit of their own stock. They do this because they hope that their stock will go up. And perhaps even more important, the officers and employees of pretty much all modern companies have stock ownership plans, and they own either outright stock or options on stock, and they can make a lot of money. This definitely affects a company — they can attract new employees and officers, and keep existing ones.

High frequency trading is very bad for a number of reasons. Here are some of them: https://www.politicalirony.com/2009/07/27/high-frequency-trading-legalized-theft/ Sorry Jeff, this is not just about futures or derivatives, this is about plain old stock too.

Much has been written about how the current obsession with short term stock price (as opposed to long term company health) is hurting companies and our economy. For example, it makes it more difficult to invest in infrastructure.

It also creates some very weird secondary effects. I have seen (and been part of) companies that deliberately delayed growth. Why would a company do that? Well, let’s say that a company has an opportunity to make a lot of money in a short period of time. They would of course go for it, right? Wrong! The problem is that if your company profits go up too fast, and then go down (even a little) then investors — especially ones who are focused on short term results — think that the company is in decline. Investors have been trained to want revenues and profits that rise steadily, and they punish (severely) companies whose profits fluctuate.

Think about it. If you were about to buy a stock and looked at a company and their revenues or profits had dropped, wouldn’t you be less likely to buy that stock? So companies will deliberately NOT make money so that they can keep their profits on a smooth upward path, with as little fluctuations as possible. It is weird, but it happens all the time. Even a small drop in stock price can cause automatic triggering in computerized trading algorithms, who then sell, further depressing the stock price. When this happens, people lose confidence. When it happens to all stocks, it is called a stock market crash.

Michael: “Really? Then why do stock prices magically jump or dive whenever quarterly earnings are announced?”

Because people are willing to pay more or less for a stock based on quarterly earnings which may reflect the value of a company to other investors. Emphasis on may. There is no 100% bulletproof investing method in the stock market. Stocks don’t always rise or fall based on the QE reports.

Stock prices also fluctuate on news, both real and imagined. It is the psychological effect on the investors that work the stock market, because a stock is only worth what someone else is willing to pay for it.

Case in point would be several of the giant firms that went under during 2008/2009. Their stock prices got absolutely smashed. Their future was uncertain. However, plenty of people invested and then sold. Some people got filthy rich for pennies on the dollar. Some people lost a ton of money. If the actual financial state of the companies was directly reflected in the stock price, it would be impossible to make money off of them and nobody would have touched them.

IK: I don’t particularly disagree with anything you said, I’m just not sure how it relates to the original post. Certainly a company cares about its stock price, for a variety of reasons. If nothing else, it has an obligation to answer to shareholders. But what does a company care about how long people are holding on to the stock?

As I said previously, I don’t understand what this has to do with people trading too quickly on the stock market. The only explanation I see in the original post of what the problem is seems to be that people are making money “too fast.” That if you make money in a second, it is bad, but if you make money in 10 years, it is good. That people who make money in one second didn’t earn it, but people who made it in 10 years did.

Maybe we could start by simply answering: if trading too quickly has a negative effect, to whom is that effect applied?

1032, I wasn’t arguing against your point that stock price is determined by market value as influenced by perception. I simply felt that you overestimate the independence between stock prices and company actions. Company actions affect quarterly earnings, which affect stock prices, which further influence the actions of executives who control company actions. They may be secondary effects, but these events are VERY tightly coupled.

I won’t speak for IK, but my own view is that the problem of quick trading is more of a symptom of deeper cultural issues than a problem in its own right. I realize that this is an extremely naive ideal, but I believe that the value of one’s work should be representative of one’s contribution to society. Yes, let the free market determine the value of that contribution. I agree with that. But I believe it is unethical to earn money from work that produces nothing of value. And that’s what high-frequency trading is. It’s profiting from the fact that claims of ownership trade hands while contributing nothing to the process.

And that’s where the difference lies between high-frequency trading and long-term, direct investment. Long-term investments are intended to help a company produce goods in exchange for a share of the profits.

IK – I understand and had thought I’d made the connection to my TV analogy with the offerings, perhaps I wasn’t clear enough.

Day traders IMO are not much different then gamblers, there is almost no way to predict how a stock will move up or down in todays 24/7 news world. I don’t know the exact statistics, but from the boom in day traders from the late 90’s to now I’d have to say the number has gone down. I’d also speculate that more day traders lose money then make money. Where we would have to look more at short term traders ability to adversly effect markets would be on the gambling trades affecting stocks, ie short sellers and short options traders. These folks like futures traders can impact the market. They typically do not own the stock unless the lose. By nature these are shorter duration contracts of 30 days or less. And as Ebdoug pointed out they taxed as normal income.

Michael: “But I believe it is unethical to earn money from work that produces nothing of value. And that’s what high-frequency trading is. It’s profiting from the fact that claims of ownership trade hands while contributing nothing to the process.

And that’s where the difference lies between high-frequency trading and long-term, direct investment. Long-term investments are intended to help a company produce goods in exchange for a share of the profits.”

I appreciate your view of ethics, but my problem is with drawing distinctions between short term and long term gains. It sounds more like you are in favor of eliminating secondary markets all together. As well as casinos! 🙂 And middlemen…

I can say without hesitation that most all my stock positions are long. Perhaps not 10 years long, but long none-the-less. I can also say without hesitation that none of my positions were purchased in order to help a company produce goods. They were all purchased with the goal of growing my bank account. I would dare say that barring friend/family businesses, the majority of investments follow this same philosophy. Even small business investment. I’m not sure many people would want to invest a chunk of money in a small business, have it grow exponentially into a monster, and receive back their initial deposit. They want the business to grow, but only because those gains will be reflected in their bank accounts.

Lets flip it around: many people who practice a “going down with the ship” mentality in the stock market lose big, because you can always buy back in if you get out. Often knowing when to sell is more difficult to know and more important to follow than knowing when to buy.

So, is it more ethical or “better” to lose money on a long term investment than to lose money on a short term investment?

I suggest that if we are no longer able to distinguish between ethical and/or better in this situation, then the root of the problem lies in the ability to make a quick buck and not with the speed of the transaction.

The root cause of our sick economy and society is the ruination of our progressive income tax system since Eisenhower, when it was 90 percent on high incomes. This induced rip offs to run their enterprises into rhe ground for maximum short term gains and bonuses, exporting jobs in the process.

Knee,

Had to take this opportunity to agree with you.

Want to really stabilize the economy? Start taxing capital gains on residences (again).

This last housing bubble was not entirely coincidental.

I had a client who bought Corning, sold at a profit, bought back. Could not understand that he had to report the gain since he used the money to buy it right back. Had no record of what he paid his broker to sell it (his stock was worth 2K) Seems broker got $186 for the trade. I got testy and told him that if he didn’t find the basis for the stock for me, I’d just put on his tax return the whole amount he received in the sale. He continues to do this (and continues to lose his huge brokerage fees). He now brings the basis. He last sold three days before the stock would be long term. Broker didn’t tell him for the huge fee he got. Corning is supposed to surge now. I hope he holds.

Another client got 1 million in a settlement. She gave it to a broker to invest. He told her she could spend as much as she wanted. He kept taking his huge fees and giving her very little yield. She should have had 30K a year. (she got no where near that) She’d take 40K. It soon was gone. As she says , “My broker built himself a nice house.”

I should add since we are “celebrating” the actor’s birthday: Long term gain during the Reagan ERA went from two years to one year(except for cows). Now ponder that because he was encouraging people to wait only one year to sell instead of two years.

Russell – The biggest source of retirement for many seniors is their house. Taxing that money won’t solve the housing bubble. Housing prices have taken care of that for most of the country in their current depressed state. The bubble was caused by greedy buyers and complicit lenders. Thats the real problem not that a 70 yr old gets to keep 250k tax free so you and I don’t have to pay to keep them going.

Capital gains are still applied to investment (none primary residences)properties.

Patriot,

Capital gains (and even sales tax) on real estate won’t fix a housing bubble. But they DO help prevent them. The number of businesses on the housing speculation tit (and their lobbyists) was astounding. Agents, mortgage brokers, banks, builders, retailers, etc. At the peak (2004) 20% of ALL discretionary consumer dollars were from refinancing home equity.

IIRC, IK’s basic idea was to reduce cap gains more progressively with time. Grandma’s old house would not take much of a hit, if at all.

Yes, tax the trades. It is interstate commerce. It is a source of revenue. It can move America from focusing on the nightly Dow Jones ticker to a longer focus on research, development, manufacturing and marketing. The selling of something real and tangible to people outside the USA. Thus, eventually curing our balance of trade before a US Dollar is worth less than a Russian red cent.

We have to compete on the world market with ideas and products. NOT with armies in distant lands.

I know one thing, this proposal will not be backed by the Republicans, because it shifts the focus from arbitrage and instant gratification, which generates piles of cash. Piles of which they syphon off in the form of donations to their cause, speaking fees, goverment contracts for their buds and lucrative “no bribes” for being part of this or that conservative “think” thank.

Such a sound proposal, as outlined above would shift America’s focus to working for a better and more competitive long term future. Probably way to sound in the long term to be adopted by the short term driven American political system.

Russell – your right, I re-read the post and your point makes sense.

But, as a law it would be like making the fine for speeding $1000 to discourage the behavior, just a bit over the top? It’s like cigarettes in my mind, Gov say ok you can smoke, but we’ll put a $3/pack tax. Why not outlaw cigarettes? Because it’s a cash cow to the govt, why not outlaw day trading? It makes the gov money. We don’t like it, but like gambling (which is what day trading is)it’s legal because it makes the govt money.

Just my opinion.

My original proposal to my brother Fred seems to have generated an interesting discussion train. Obviously it was off-the-cuff but being a businessman involved in production as well as marketing it is sometimes frustrating to see such a huge share of our GNP derived from simply moving money from hand to hand. The primer earners are not the investor, they are the people moving the money since they get to skim a penny or two from every dollar no matter how long they hold it or who they send it on to. This is certainly human nature and there are plenty of natural organisms that do the same thing. In fact I got my PhD from Berkeley studying those organisms. They are called “parasites”. Again perfectly natural but somewhat distastful as a way of life.

The basis for my idea actually came from a scheme I had developed to encourage the use of forestry for wastewater treatment. I had to do with carbon storage and a way to value it. I called it the Carbon Storage Half-Life. Namely if you plant a forest and harvest part of it as Christmas trees in 5 years you get a certain credit since the carbon will be stored for some average time that includes the time in the forest and the time it still exists as a tree before being burned. The same forest harvested for paper would get a larger credit since the trees will be older and the paper product will stick around for several years also. Similarly if the product is harvested as timber at 30 years and sits in a house as a wall for 50 years. Maximum credit would go to the forest that is planted and maintained as a park or natural habitat, obviously keeping the carbon out of the atmosphere for the longest time. Again, this would be complicated, but quantification of these things is possible as any trained ecologist can tell you.

Hi Dan! Welcome.

I think your idea could work. For too long our country (as most other countries do) has taxed things that we should want to encourage (like earning money, buying things, etc.) and not taxed things we want to discourage (pollution, causing bubbles through speculation, etc.). Changing that would be a great way to overcome one of the major problems of modern capitalism — that it does not account for problematic externalities.

“Parasites”: exactly! High Frequency Trading (HFT) provides absolutely no net benefit to society. The claim is that it provides liquidity; in other words, they are the buyer or seller of last resort. However, the May “Flash Crash” defeated that argument: the HFTS stopped trading, as long with everyone else. A simple and easy to implement rule is that every trade placed must be valid for at least 1 second. Bye, bye HFT.

BTW HFTs do not make the governement ridher: they just make the lobbyist and legislature richer.

One Trackback/Pingback

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Jonathan Borzilleri, joe mackenzie. joe mackenzie said: Asymptotic Trading: [This is an excerpt from a post in Fred Wickham's Bullseye Rooster. Dan is Fred's brother, a… http://bit.ly/fobfUH […]